- Home

- Jacek Dukaj

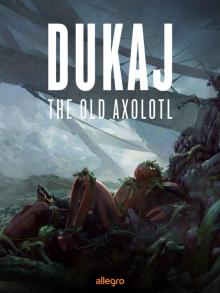

The Old Axolotl: Hardware Dreams Page 8

The Old Axolotl: Hardware Dreams Read online

Page 8

“If we breed them and raise them to be IT experts, they can set up virtual realities for us so that we won’t have to torture ourselves with metal in the material world anymore.”

“And they’ll play us on their consoles in the playrooms of eternity.”

They soared over the green fields of America, the black sails carrying them higher and farther. Imperceptibly, they had left MIT and New England behind, and Bartek knew now that all this greenery was due to the Morpheus, since their biospheric reboot didn’t extend this far – across the Rust Belt, out over the Great Lakes, and down the Mississippi River. It was both night and day, and a crisp light illuminated the fresh forests and life-colored fields – ah, they skipped over the Gulf of Mexico and the Panama Canal – and now at eighty percent dream immersion, in a flock of heavy assault axolotls, they struck Rio de Janeiro and Campinas, the server rooms of the Patagonia Riders and their mech workshops, the axolotls spitting out bombs in the shape of smaller axolotls, which then spat themselves out into even smaller ambystomas, so that the whole fractal raid of amphibians fanned out oneirically until a fiery rain slammed into the daytime/night-time continent on a thousand rainbows, while Bartek found himself dreaming in orbit, where the axolotls liked to meditate on eternity and humanity, and from this roost of angels he clearly saw the two atomic mushroom clouds erupt over southern Europe, and even sleep-morphed to the max he understood that before his very eyes, in his dream, the Second Transformer War had broken out and was raging across the globe. All the while, he sobbed out his Ural depression onto Rory’s shoulder.

War, war never changes

He slid the Morpheus potentiometer down to zero, trembling with the purest of all solipsistic fears – that he might be dreaming his awakening as well.

He heaved the shell of his Honda up off the wet roof. It was a sunny afternoon after heavy rain, and the MIT campus gleamed with silver puddles and the beads of merry raindrops.

Bartek picked up a signal from the Mothernet. The date showed 10231 PostApoc. Thirteen days had passed.

Rory’s Honda hoisted itself up with the same grinding sound, probably having just restarted itself after Bartek had moved.

“I’m glad that—”

With a lightning-fast FUCK YOU! emote, he threw himself at her and knocked her off the roof. They plummeted down together onto the footpath, him on top, her striking the flagstones with her side, so that the crash rocked the entire campus. Bartek-Lily’s hip joints were crushed and his left arm was severed; Frances-Lily was snapped in two like a broken doll. The local Matternet wailed in red.

“How did you get the passwords?!” demanded Bartek, pounding at the upper half of the Honda Spirit until the feathery steel cover of the radiator came off. “Where did you get the passwords?! How did you hack into me?!”

“No – body – hacked – into - you,” grunted Rory in time with the slamming of her head against the concrete. “We – slowed – down – your – whole – ser - ver.”

He let her go.

The whole time she had distracted him with her chatter to stop him from working it out. If not for the sleep-morphing, he’d have noticed much earlier.

He had refused to slow down, as the Iguarte Zodiac dictated, so they had slowed him down on the sly, without his consent.

Two babysitter mechs were leaning over them. From behind their chimney-stack legs peered the little face of a girl from the Third Litter, staring with the big eyes of a very serious child. It was Milenka.

Frances propped herself up on an elbow.

“Sorry, I had no choice. Cho would have torpedoed the negotiations just to show who’s boss. You stood up to him at the worst possible moment.”

“Bullshit. You wanted me off the scene because you were scared that Dagenskyoll had talked me into voting for the Royalists and Big Castle.”

“Sorry.”

Bartek awkwardly gathered up pieces of hardware from the concrete. Parts of breastplate and sub-assemblies spilled between his fingers.

He didn’t even feel like emoting.

“So what was the decision?”

“Heavy Metal went down, Homo sapiens won the day. We’re making humanity.”

The Second Transformer War had been a religious war.

“I’m out of here,” said Bartek. With an ugly screech, he heaved himself into an upright position and popped a stray lens back into its eye socket. “You’ll have to get by without me.”

“Where are you going?”

“Somewhere on the independent servers.”

“There are no independent servers.”

“I’ll make one. I’ve got sealed stores of spare parts.”

“Okay,” said Frances, apologetically emoting a beaten little dog. “Just don’t get mad again.” She performed a deep intake of breath – fully human and organic. “We’ve got your backups.”

Red sparks fizzed out of his torn-off arm.

“You stole me!”

“We had to. Until we start raising nerds two zero.”

Milenka was deep in thought, her expression evidently copied straight from Pixar toddlers and dogs, as she placed one piece of shattered Honda after another onto the crippled torsos that lay on the devastated footpath – cables, armor plating, engines, steel fingers, and polymer bones – biting her little tongue and blowing her bangs out of her eyes.

“Why are you fighting?”

“Auntie played a little trick on uncle.”

The problem of epigenesis kept Bartek from getting any shut-eye at night (not that he had eyes to shut, but the feeling was the same).

So what did he do while he wasn’t sleeping? He watched thousands of hours of recordings – from Paradise, from before the Extermination, and from the lives of the second humans of the early litters, born via Vincent Cho’s method of synthesis from the preserved genetic archives.

Thousands and tens of thousands of hours. Tirelessly comparing: children and children, life and life, words and words, laughter and laughter, games and games. But what was the difference? Was there any difference at all? Or was the error in the eye of the beholder and the cause in another difference entirely – the difference between man and transformer?

Epigenesis evades all technical analysis.

“You take exactly the same DNA,” Jarlinka explained. “You implant it and develop it in exactly the same conditions, and you can still end up with different organisms.”

“So in the end they’re not humans? I mean, not like before the Extermination?”

“Well, the genome is the same. But the different types of gene expression – which genes activate, which don’t, and at what stages – all that is stored outside the DNA, in the stream of intergenerational memory. It all starts with the histones – take a look, they’re these proteins here. The DNA wraps around them like spaghetti on a spatula, but it’s the shape of the spatula that determines the shape of the wrapped DNA. So what does it matter that you have the same genes when you don’t know what kind of spatula to serve up in the first place? Or the whole process of methylation. Have you read that methylation imprints DNA with your whole lifestyle, all your traumas and illnesses, your material status, education, place of residence, the air that you breathe? Or take hereditary environmental expressions. Or—”

“So genes have their own culture.”

“Huh?”

“Take a man out of culture, raise him in the wild, and you’ll end up with an animal, not a man. Culture is not encoded in the DNA.”

Before the Extermination, Jarlinka had sold comic books in New York. His interest in genetics had begun with the Incredible Hulk and Spider-Man.

“But we’ve preserved culture!” he said, shoving a pile of Batman and Iron Man comics into Bartek’s face. Jarlinka had all the first editions of the world in his collection. He would never change, never grow out of his teenage geekiness. “We’re raising them on the same stuff that we were raised on.”

“We? You mean our originals?”

Bartek ha

d watched thousands of hours of recordings, including recordings of himself, from parties that he usually couldn’t even remember, city archives, work functions, other people’s videos from Facebook. He had stared at himself – himself in the body of Bartek 1.0 – and tried to feel his way into the old humanity.

But how was he supposed to emote this humanity today? And what had been irretrievably lost, somewhere between feeling and emoting?

“What an absurd question!” exploded Jarlinka. “There is no ‘between.’ Where would it be? We express anger and joy with emotes, we cry with emotes, and we love with emotes. Emotes are our feelings.”

But Bartek still remembered 1K PostApoc in Tokyo, with all those shatteringly sad performances of humanity played out by transformers turned into graceless mechs, with their clumsy simulations of drunkenness at the bar in Chūō Akachōchin, the heartrending parodies of tenderness converted into tons of metal and the megajoules of servomotors, the rituals of biological buddyhood cultivated in the forms of awkward machines; how they chinked glasses filled with alcohol they couldn’t drink; how they gaped at pornography that couldn’t evoke the least desire in them; how they turned up their speakers to crank up the atmosphere of a conversation. He remembered it perfectly, because he had recorded it.

And now, at 10K PostApoc, they no longer even tried to simulate simulation or pretend to pretend, when there was no need and nobody was watching.

So what did they do when they weren’t working or watching films from Paradise?

Nothing.

They were statues of cold metal. Robots out of work.

“The thing is,” said Bartek, trying to explain himself to Jarlinka while his display spat out a hodgepodge of stroboscopic associations, “that in a few years’ time, they’ll start to multiply and raise their own children, the first/second litter, and then all this will inevitably copy itself down through all the generations to come. Just as in the first instant after the Big Bang a microscopic quantum irregularity determined the shape of whole galaxies and clusters of galaxies, so right now those few years of their childhood – the games, lullabies, nannies, fairy tales, punishments and rewards – will determine the shape of Humanity 2.0 and beyond.”

Jarlinka emoted the shrugging of a thousand shoulders with his Burg.

“Well, then go and play with them.”

Alicia was five years old and she always recognized Bartek from the subconscious subtleties of his behavior, no matter which mech he happened to have chosen. Sometimes he wouldn’t even have emoted anything, or said anything, and she would run straight to him, climb up onto his slashed steel plates, and doodle in marker pen all over his head and display.

“We going hurray!”

“We’re going to go hurray.”

We will be friends until forever, just you wait and see

Bartek had manifested in a municipal Taurus, which had a huge blower nozzle instead of a right hand. They walked out onto Vassar Street, towards the western end of the campus, behind the overgrown and waterlogged baseball fields, already covered with an autumnal coating of leaves from the first 2.0 trees, which Cho had planted zealously in the early days of the tests. Now a maple-like species with a bark unknown to the natural world of Paradise was growing in Cambridgeport. There were also self-stunting little oak trees, like bonsai, and weedy bushes resembling regurgitated wigs – the ludicrous mistakes of neo-flora that could never be eradicated.

Bartek blasted a small hurricane from the gaping maw of his right hand, raising colorful clouds of leaves and driving them systematically into the corner of the Westgate courtyard onto a former parking lot. Alicia frolicked in the rustling clouds, waving her arms like windmills, while her irigotchi – Autumn Glory and Flea Circus, the latter apparently superimposed on the former – raced around the swirling leaves like Disney puppies, all the while twittering out the poetry of the previous century’s advertising jingles.

At the foot of a crumbling skyscraper, Bartek met Dagenskyoll.

“Does this piece of junk of yours pick up ultrasound?”

“Don’t worry. The little one won’t hear anything. You’re drowning everything out with your roaring fist.”

“She won’t hear anything, and she wouldn’t understand anyway, but the irigotchi are more and more tightly linked with the Matternet. Cho has ears everywhere.”

“Now you’re the one who’s paranoid.”

“Just wait,” said Bartek, before he really did switch to ultrasound, “till I give you the reasons for my paranoia.”

“They can’t screw us more than they’ve already screwed us,” rumbled Dagenskyoll, emoting a fuck-off at the Bully Boys, the Dwarves, and the whole of Project Genesis.

“So what then? Are you going to just lie down and wait for the deluge?”

“Ha! Right now they’re drawing up the orbital planes at Big Castle. See, you gotta put up some new satellites, rebuild the global communications network, and then trade on the monopoly.”

“I can just see it now. Suddenly they whip an army of space engineers out of their sleeve. How many transformers were rocket fuel experts in Paradise? You’ve got to be kidding. No, no, I’ve got something else in mind.”

“What?”

“If you could just concoct some new life in the oceans after all.”

“How?”

“With your Chos, Jarlinkas, and Lagiras.”

Dagenskyoll emoted a big blank.

“Go on, go on.”

“You know what they did to me?”

“They slowed you down Ural style for the whole war. You already blubbered into my cables about it.”

“There’s more. They have my backups,” said Bartek, emoting a bitterness that seethed like the acid of alien blood. “They covered their asses, so they wouldn’t be stuck without a hardware handyman. If I want to leave, they’ll just start me up here on the backup server. Then they’ll check whether the double wants to leave too, and so on with different conditions each time until one of my selves eventually ends up deciding to stick around for good, genuinely content to be subserviently shoveling shit for Cho.”

Dagenskyoll froze in the middle of Bartek’s tirade.

“You want to come over to us…” That was all he heard.

Bartek heaved a ten-meter sigh with his nozzle. Alicia and the irigotchi chased his sigh to a crossway of paths.

“I told you: I won’t do you any good. I’m a hardware janitor. I don’t know anything about life two zero. Or about life one zero, for that matter. I know about machines.”

“So?”

“I’m a hardware janitor. I have all the keys and skeleton keys. I’m the one who cleans out the motherboards for them and scrubs the optical memory. Rory could hack into the neurosoft, but I’m down in the basement server rooms, pulling out memory drives and setting up RAIDs.”

“You’re talking about physical theft.”

“You better believe it! I don’t need to break the security software or play the IT expert – which I’m not – to twist out some screws and unplug a few Thunderbolts. Then the GOATs of the Royal Alliance will surely plow through it on their own computers in Japan via the method of brute force and you’ll open your own Chos and Carters and Jarlinkas – the whole Project Genesis team.”

“They voted against us, and you think they’d suddenly want to work for us over there?”

“Think about it. You’ll do exactly what Rory did to checkmate me. You’ll keep starting up Cho over and over, again and again, until one of the versions decides for itself that it wants to repeat the creation of the world with you. I’d even be willing to bet on its motivations: Humph, I’m not that Cho, I’m a different Cho, a better Cho, the best Cho, and now I’m going to show old Vincent how to make life!”

“And what, then there’ll be two Genesis Projects 2.0, two natures, two humanities?”

“At least two.”

In the meantime, Autumn Glory had spread across most of the networked matter on the Charles River. Dozens of iri

gotchi were bustling about at the steel feet of Bartek and Dagenskyoll, arranging the leaves and branches into beautiful fractal mandalas, like Tibetan sand mantras. Bartek immediately blew them away towards the trash heap, but this didn’t seem to bother the melancholy vector of the Matternet/irigotchi. It just began again, this time scrawling symmetrical graffiti patterns on the Mothernet surfaces of the buildings and paths. A few days earlier, Bartek had watched from the roof of the Media Lab as irigotchi vectors as large as five or even ten square kilometers flowed across the MIT Mothernet. Then at night-time they had shone as the last remaining lights on the Boston skyline.

“And you?” asked Dagenskyoll, scraping metal over Bartek’s metal in a brutal echo of the chummy affections of the body. “What’s in it for you? Apart from revenge.”

“I want the impossible, of course. The same as everybody else: a return to Paradise,” said Bartek, turning off the blower and hoisting the giggling Alicia up onto his shoulder. “If you start work from scratch on Homo sapiens, I want to raise him my way. From epigenesis to bedtime stories. Not like here. Here it was just a freestyle experiment. They didn’t know what they were doing.”

“Nobody knew the first time around, either.”

“The first time?”

“Yeah, in Paradise. Evolution. From the amoeba. The natural history of mankind. That was pretty much freestyle, wasn’t it?”

Bartek paused in a meaningful silence (no emote was still a kind of emote).

“Do you know what the ‘minuses’ are in Project slang? I’d show you if we had time. Jarlinka keeps them in formaldehyde next to his comics. Some of them even look like that: straight out of Marvel. They treat litter number one like the birth of Christ. It was only years later that they started to clock the whole Project back to it, recombination after recombination. Before that, they’d racked up more than a dozen botched attempts at epigenesis. In theory, the DNA was all hunky-dory, but it gave birth to a monster. Or it didn’t make it that far, just withering away in the incubator womb. Those are the ‘minuses’: litters minus one, minus two, minus five, minus fifteen.”

The Old Axolotl: Hardware Dreams

The Old Axolotl: Hardware Dreams